28 April 2020

3 min read

Researchers followed hot on the heels of a major cyclone that hit a Pacific island during the coronavirus pandemic, mapping the damage within hours.

The detailed insight to damage to infrastructure, including roads and bridges, helped direct relief effort to the places most in need of help.

The team of emergency management, community resilience and disaster response experts at the University of Portsmouth, led by Dr Richard Teeuw, used satellite imagery to capture the destruction caused Cyclone Harold earlier this month on the island of Vanuatu.

Vanuatu is a beautiful country, with a very welcoming people, but also very susceptible to disasters.

Dr Richard Teeuw, Geomorphologist and remote sensing scientist

The cyclone was one of the most severe storms ever to hit the region.

Dr Teeuw said: “Rapidly mapping the impacts of a severe storm, including flooding, erosion, landslides and debris flows on the island’s critical infrastructure allows us to map damage very quickly, helping the relief effort target its help to where it’s needed fast.

“Vanuatu is a beautiful country, with a very welcoming people, but also very susceptible to disasters.

“We hope that by rapidly assessing satellite imagery to map roads and bridges damaged by the cyclone is a useful contribution to disaster relief.”

The cyclone struck Vanuatu during the coronavirus pandemic, further complicating recovery and the delivery of aid.

Dr Teeuw said: “The cyclone meant thousands of people lost their homes and had to move into cramped storm shelters at a time when almost every country was asking people to socially distance, to help contain the disease.

“Covid 19 quarantine measures might also have an impact on the international disaster response teams and slow the distribution of overseas aid cargo.”

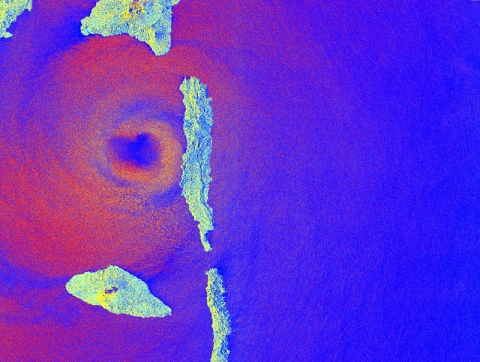

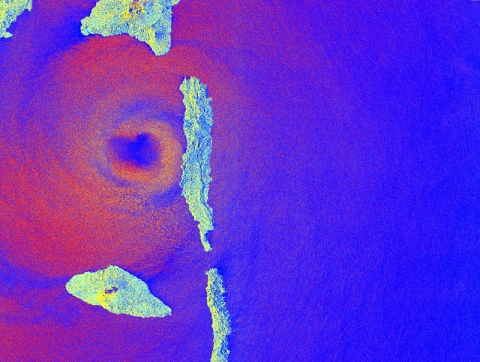

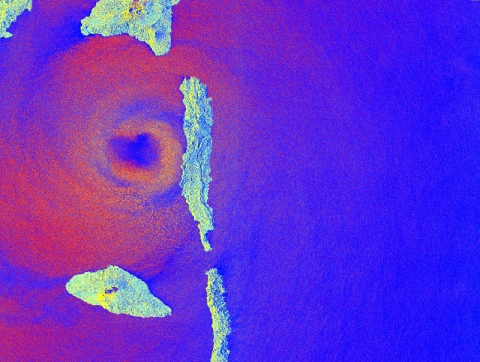

The cyclone hit the northern Vanuatu islands of Espiritu Santo and Pentecost as a Category 5 storm – the most powerful and destructive, with sustained winds of 215km/h and gusts of up to 235km/h. Satellite radar image captures the eye of the storm’s landfall on Pentecost Island, the direct hit causing widespread devastation.

The team used satellite imagery from Planetscope. In its imagery, pixel size is about 3.8 metres, which doesn’t allow for an accurate assessment of damage to buildings but does give scientists the ability to map flooding, erosion and landslides and damage to roads or bridges.

“Its imagery has some limitations: It is not detailed enough for mapping sub-metre features and the imagery cannot ‘see’ through cloud cover,” Dr Teeuw said. “Fortunately, after a major cyclone, there are often relatively cloud-free skies and the daily (sometimes twice-daily) orbital coverage of the Planetscope satellites can then provide some relatively cloud-free imagery.”

It is estimated half the island’s 320,000 population was affected by the cyclone, with four dead and many more injured.

Satellite imagery showed 90 per cent of buildings on one island were damaged.

Eye of the storm: A satellite captures the moment Cyclone Harold arrived at Pentecost Island, Vanuatu, on April 6, 2020 (data source: the European Space Agency, ESA; processed by Dr Mathias Leidig, University of Portsmouth)

The Portsmouth researchers who volunteered to help in the disaster response effort were working on the CommonSensing project, funded by the International Partnership Programme of the UK Space Agency.

Their efforts were in conjunction with the UNOSAT team of the United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR) which specialises in rapid post-disaster damage mapping, particularly the severity and extent of building damage. UNOSAT coordinated other emergency mapping teams to interpret the 0.5m pixel satellite imagery.

Cyclone Harold started in the southern Solomon Islands, becoming a Category 5 storm when it hit northern Vanuatu. It hit Fiji and Tonga as a Category 4 storm before weakening to a tropical storm.