Thousands of lives could potentially be saved if paramedics were given clear guidelines for giving intravenous antibiotics to patients with suspected sepsis, according to new research.

Sepsis kills fast, and every hour treatment is delayed costs lives.

Last year, in the UK, 44,000 people died of sepsis, more than those who died from bowel, prostate and breast cancer combined.

The number of people killed is halved if treatment starts within an hour of severe sepsis being diagnosed.

Patryk Jadzinski, a paramedic lecturer at the University of Portsmouth, published his small-scale study in the Journal of Paramedic Practice.

He said: “According to the already published research, every hour treatment for sepsis is brought forward improves a person’s chances of staying alive, so we wanted to examine how ambulance services across the country approach this, in the absence of national guidelines or standards.

“Paramedics can and do spot sepsis in their patients – according to data from the Isle of Wight they’ve been shown to be 93 per cent accurate in diagnosing it. Pre-hospital clinicians can and do sometimes face long delays getting that patient to hospital. We wanted to examine what barriers might be stopping a uniform, nationwide protocol to support paramedics in delivering antibiotics in that critical first hour.”

Paramedics don’t routinely administer intravenous antibiotics to patients they believe are suffering from sepsis, but very few areas of the UK practise that approach.

Medical directors at five of the UK’s 14 NHS ambulance services were interviewed for the study, which found widespread differences in their opinions on how intravenous antibiotics should be used out of hospital, to treat suspected sepsis.

The research, co-authored with Dr Chris Markham, also at the University of Portsmouth, found there was a drive for early sepsis diagnosis and pre-alerting the receiving hospital, but without evidence, decision-makers were reluctant to consider a standard UK-wide approach using intravenous antibiotics.

Even though paramedics are often first to recognise sepsis, and there is a drive for early sepsis diagnosis and pre-alerting the receiving hospital, the evidence base and the treatment available in the UK for pre-hospital sepsis are limited.

Patryk Jadzinski, Lecturer in paramedics

“Even though paramedics are often first to recognise sepsis, and there is a drive for early sepsis diagnosis and pre-alerting the receiving hospital, the evidence base and the treatment available in the UK for pre-hospital sepsis are limited,” Mr Jadzinski said.

The ambulance medical directors’ responses ranged from being cautious about paramedics taking blood and administering intravenous antibiotics, to a belief that to do so carried little risk and potential significant benefits and could be used.

Most agreed it would be difficult to agree which antibiotic to use across all UK ambulance services.

In 2017, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) called for more research on the treatment of sepsis.

Intravenous antibiotics are not routinely given by paramedics for the treatment of sepsis, however there is substantial in-hospital data suggesting early intravenous antibiotic administration results in fewer deaths.

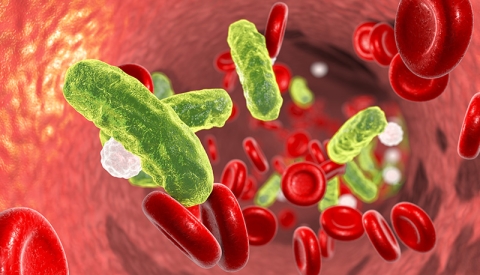

Sepsis is a critical complication of an infection, which, if left untreated, can lead to death. In its advanced stage, as a result of an organism's response to an infection, it damages tissues and organs. In further stages, sepsis can lead to septic shock, and multiple organ failure.