On World Human Rights Day, English Literature Scholar Dr Christine Berberich reflects on Wells’s pioneering contributions

5 min read

Today, 10 December, is the International Day of Human Rights. The significance of this day, always high, is of particular importance in a political climate that across the world sees a worrying rise in anti-refugee and anti-immigrant sentiments that often comes at the expense of safeguarding human rights. The day is also an opportunity to once again consider and celebrate the important literary connections in Portsmouth, and recognise the enormous contribution of H.G. Wells to the conception of the U.N. Declaration of Human Rights.

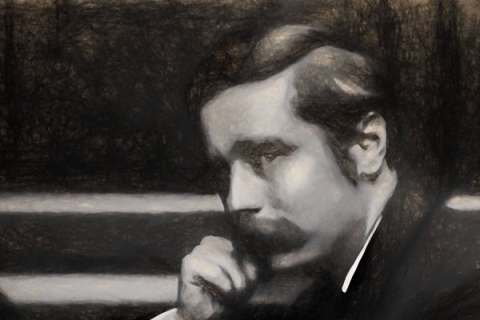

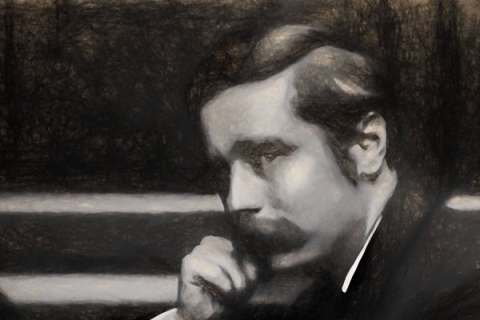

The Author (and Portsmouth)

Herbert George Wells (1866–1946) is now mostly remembered as one of the principal creators of the scientific romance, and as the author of science-fiction favourites as The Time Machine (1895) or The War of the Worlds (1898) as well as his realist fiction such as Kipps. The Story of a Simple Soul (1905) or Tono-Bungay (1909). Born in Bromley, Kent, he lived in Southsea between 1881 and 1883, where he was apprenticed at the Southsea Draper’s Emporium on the corner of King’s Road and St Paul’s Road, a time and location he regards with considerable distaste, recalling, both in novels (in particular in Kipps) and, as featured on the Portsmouth Literary Map, in his autobiographical work Experiment with Autobiography (1934), the dreariness and drudgery of his apprentice years.

The Rights of Man

While Wells has, over the decades, attracted millions of loyal readers and is well-established within popular culture, his considerable contributions to human rights are little-known and deserving of much greater recognition. In 1940, Wells published The Rights of Man, a tract inspired by the beginnings of the Second World War and his fears for the future. Always politically progressive, Wells fearlessly argued for the protection of equal rights for every man, woman, and child irrespective of background, race or creed. In 1940, Wells was also one of the most important contributors to the Sankey Declaration of the Rights of Man under the chairmanship of John Sankey, first Viscount Sankey, a British Labour politician, judge and legal practitioner who was Lord High Chancellor between 1929 and 1935.

A Declaration of the Rights of Man

The Declaration established eleven fundamental human rights: the right to life, the protection of minors, the duty to the community, the right to knowledge, the freedom of thought and worship, the right to work, the right to personal property, freedom of movement, personal liberty, freedom from violence and the right of law-making. Although the creation of the UN’s Declaration of Human Rights is generally credited to the Canadian John Peter Humphrey and the Frenchman René Cassin, Humphrey himself, in his book Human Rights and the United Nations: A Great Adventure (1984), admits that the Sankey Declaration and a document by Wells were among the sources he consulted for his own draft of the declaration.

The Universal Declaration for Human Rights was adopted by the UN General Assembly on 10 December 1948 in Paris in a response to the destruction caused by the Second World War and the horrors of the Holocaust. It promised to uphold and protect the rights of every human being that could not be taken away by any other individual or state. Of the 58 member nations at the time, none voted against it. The text of the declaration is worth reading:

“All human beings are born with equal and inalienable rights and fundamental freedoms. The United Nations is committed to upholding, promoting and protecting the human rights of every individual. This commitment stems from the United Nations Charter, which reaffirms the faith of the peoples of the world in fundamental human rights and in the dignity and worth of the human person. In the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the United Nations has stated in clear and simple terms the rights which belong equally to every person. These rights belong to you. They are your rights. Familiarize yourself with them. Help to promote and defend them for yourself as well as for your fellow human beings”.

― United Nations, Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Wells’s Vision, and human rights today

HG Wells was a real visionary, a man ahead of his time, who strongly believed not only in human rights, but also that the secret to future peace lay in the creation of a League of Nations rather than in protecting individual nation states. He passionately fought for the freedom of movement of each and every individual, including the right to cross borders and to settle freely. 81 years after the publication of The Rights of Man, Wells would undoubtedly be dismayed by an increasing return to shoring up borders, by the curtailment of freedom and movement, and, in particular, by the current British government’s threat to abolish the Human Rights Act that was only passed in 1998. At a time when millions of people are trying to flee war, persecution, starvation, or climate crisis, when desperate people take to flimsy boats to cross seas, and when men, women, and children freeze to death in makeshift camps along Europe’s borders or drown in the English Channel, it is not enough to simply have a World Human Rights Act. What is needed as we reflect on this International Day of Human Rights are people as passionate about upholding and fighting for Human Rights as Herbert George Wells was during his lifetime.

Dr Christine Berberich is a Reader in English Literature at the University of Portsmouth, specialising in Holocaust Literature, fictions of Englishness and national identity, and Brexit Literature. She is also Associate Head (Global) at the School of Area Studies, Politics, History, and Literature. She is the author of The Image of the English Gentleman in Twentieth-Century Literature (Ashgate 2007) and the editor of The Bloomsbury Introduction to Popular Fiction (Bloomsbury, 2014), Trauma & Memory: The Holocaust in Contemporary Culture (Routledge, 2021), and Brexit and the Migrant Voice: EU Citizens in post-Brexit Literature and Culture (Routledge, forthcoming), as well as numerous journal articles.