This talk commemorates Juneteenth and brings together a virtual discussion about labour migration and labour rights in global supply chains.

Join the University of Portsmouth's Interdisciplinary Webinar Series, chaired by Leïla Choukroune, Professor of International Law and Director of the University of Portsmouth Thematic Area in Democratic Citizenship, and presented by Dr Bonny Ling, Advisory Board Member of Human Rights at Sea.

Each year, the 19 June (Juneteenth) commemorates the abolition of slavery in the United States, which took place with President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 and the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1865. The ending of the American chapter of chattel slavery — the legal ownership of a person by another as if the person is property of the other — thus forms a link in a long chain of key anti-slavery events in the nineteenth century.

The global abolition of chattel slavery, however, is not the end of appalling human treatment. It is the beginning of another chapter of exploitation that extends to present-day efforts against “modern slavery” and human trafficking in all its forms. This talk explores this further.

Speaker’s bio

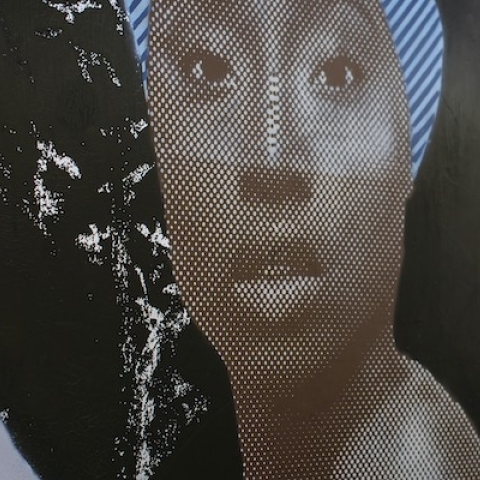

Dr. Bonny Ling is an Advisory Board Member of Human Rights at Sea, an international NGO that raises awareness of human rights abuses in the maritime sector and delivers social justice through legal and policy development; and a Research Fellow with the business think-tank, Institute for Human Rights and Business. Previously at the Centre for Human Rights Studies, University of Zurich in Switzerland from 2014–2019, she is an independent researcher affiliated with the Cambridge Centre for Applied Research in Human Trafficking for her work and research on human trafficking.

She has worked in the UN system and in international civil society. She holds a Ph.D in Law from the Irish Centre for Human Rights, M.Phil (Cantab) in Criminology and MA in Law and Diplomacy from the Fletcher School, Tufts University. She also consults as a legal analyst on responsible business conduct with a focus on Asia; and has served as an international election observer in East Timor and for the OSCE. She writes on human rights, migrants, business responsibilities and international relations and development.

To watch the Webinar please follow the link.